Day 1

Have you ever flown from Heathrow to Buenos Aires with 30 wine merchants? It’s an experience I would recommend, although the lounge at Terminal 5 and British Airways might still be reeling from the drinks tab we managed to knock up.

It’s a rare opportunity, that we get to visit any of the world’s more far flung wine regions, so when I was invited to go on a trans-Andean tour of Chile and Argentina by Zuccardi and Vinedo Chadwick, I grasped the opportunity with both hands, feet and any other available appendage.

Our flight(s) were punctuated by a short bus journey across BA, to what I assume is their equivalent of Luton or Stansted, from where we were able to catch both our transfer to Mendoza and most of England’s (disappointing) six nations performance in an airport bar.

The whole trip was nearly 20 hours long, so when we finally got to our hotel, we had an hour or so for a quick dip in the pool, which happened to be my first encounter with Eduardo Chadwick. It would have been slightly unmanning to have bumped into the most powerful man in Chilean wine even with my top on, but it leant a certain honesty to our conversation, and he was polite enough not to recoil at the sight of my hairy chest.

I will not divulge here what he thought of the future of Chilean wine, or who he considered to be the most up-and-coming producers in the country – for that information, you will have to suffer my direct contact, but it was clear from our first contact that he is (justifiably) confident in his own product.

Following this quite literal cooling off period, we were bundled back onto the bus for an hour or so drive to Zuccardi’s Bodega Santa Julia winery, just outside Mendoza. Here, stood in a courtyard, under a huge canopy of vines (from which you could just reach up and pluck delicious ripe grapes) we met the family.

Following this quite literal cooling off period, we were bundled back onto the bus for an hour or so drive to Zuccardi’s Bodega Santa Julia winery, just outside Mendoza. Here, stood in a courtyard, under a huge canopy of vines (from which you could just reach up and pluck delicious ripe grapes) we met the family.

It is truly a challenge to express the enthusiasm of both Jose Alberto and Sebastien Zuccardi in words. Perhaps we were just feeling terribly British and a bit tired, but to be given a big hug by them both, along with their extended family, upon arrival (along with a glass of their secretly quite tasty sparkling wine) goes a small way to showing just how joyful they are.

The Zuccardi family, much like most of the fine wine world, made their money elsewhere before really taking on the challenge of vines. Engineering was their path before the grape, a skill which Sebastian later attributed some of their success to (setting up vineyards in Argentina, with all the irrigation required, is no mean feat).

Having thirstily consumed that first glass, we were taken through the building and into a courtyard, awash with smells, sounds and the bustle of activity. There were enough wood ovens being crewed to feed an army (they are obviously familiar with the appetites of wine merchants) and by this point it had grown dark, so the flames filled the space with a dancing light. Off to the corner, over an open fire, stood three asador grills, metal cages arranged at a slight angle to harness the flames below and slow roast the spatchcocked goats inside to perfection.

We were in our element.

‘Don’t fill up on empanadas’, I was warned by one of our guides. I stopped to briefly look at him, half way through my third one, before wolfing that down. ‘There is a lot more food to come’.

As if the ovens, fire, smells, sounds and sheer volume of food weren’t enough of an assault on our senses, behind the ovens, a storm began to gather. As the wind picked up, we were ushered inside to a very long dining table, set in a conservatory which overlooked the courtyard we had just been inhabiting. As the wine began to arrive, so did the lightning. There was no rain, even the air didn’t seem to pick up much humidity, but intermittently we would be shown some incredible natural fireworks. Sheets of pure white, or bolts of energy coursing through the sky.

Appropriate, perhaps, to come back to topic, as the first two wines we were served were Zuccardi’s 2016 Paraje reds – both named ‘Aluvional’, due to the alluvial soil on which the vines grow (I’ll get to this later because, even if you’re not a geology geek, it’s pretty interesting). One from Altamira and one from Gualtallary. I had been lucky enough, courtesy of a good friend, to have tried both of these wines before, so an I had an idea of what to expect, but it had been a year or so since then and they were even more staggeringly good than I had recalled.

To anyone who is reading this with a conventional image of Malbec – big, juicy, rich, glycolic, alcoholic, soft and rounded, I am with you. It’s how I pictured Malbec too, until I tasted these wines. But zap, like the sky outside, they hit you with a bolt of electricity. More akin to the high tone of Pinot Noir, with both the acid and structure at play. Amazingly, they still carry the signature fruit profile of Malbec, but with a thrilling sensation you so rarely get from the grape. To those not so schooled in the geography of the Uco Valley (and believe me when I say, I was in that number before this trip) the two vineyard zones from which they originate – Gualtallary and Altamira, are at opposite ends of the valley. Think of them as like Saint-Estèphe and Margaux, or Gevrey- Chambertin and Nuits-Saint-Georges.

The same grape, the same place, minimal geographical difference, but very different results in the wine. This terroir-focussed approach is at the heart of what Zuccardi are doing, and we would come to learn a lot more about it the next day.

In the meantime, we all retired to our hotel rooms – dazed by our epic voyage, and more than a few pounds heavier.

Day 2 | Part 1

Morning broke and we all met in the reception of our hotel. Zuccardi, on arrival, had very kindly furnished us all with some branded gilets (the way to win any wine merchant’s heart) and our size had been estimated by their importer (mercifully mine fit). One of the more ‘physically endowed’ gentlemen, who had made a jolly good attempt to stretch his gilet around his relatively vast form, threw out to the group with a mischievous grin that he ‘would need three of these stitched together to fit around me’. The back of the chair he was leaning on promptly broke – we beat a hasty exit.

Eschewing the big coach, we were all taken up to the Uco Valley via pickup truck. The roads got pretty rugged as we climbed every higher into the mountains, and if gilet-gate were anything to go by, the poor bus might have struggled to pull us all up there.

I attempted to ask some constructive questions of our guide, but between the brain fog of jetlag, a whisper of a hangover and the acid reflux for eating a kilo of goat, conversation was kept fairly minimal. Eventually, we hit vineyards, the first and most noticeable thing being that they were far from contiguous. Unlike Bordeaux, Burgundy or Napa, where vineyard land is gold dust, and everyone crams in to find as much land as possible, the Uco Valley, whilst perhaps Argentina’s most prestigious vineyard area, evidenced through this, that it is still globally a very ‘up and coming’ place to grow vines.

I draw only positives from sights like this. The Uco Valley is clearly an incredible place to grow wine – not just for Zuccardi, all of Argentina’s top scoring wines (indeed, referencing RobertParker.com, all of the country’s eight 100pt scoring wines) are from here. So seeing vast tracts of land unused shows either how focussed these vinous Magellan’s are on discovering the finest plots on which to grow their vines, or indeed how many of these fantastic plots remain undiscovered. Either way, it has the distinct air of opportunity.

I draw only positives from sights like this. The Uco Valley is clearly an incredible place to grow wine – not just for Zuccardi, all of Argentina’s top scoring wines (indeed, referencing RobertParker.com, all of the country’s eight 100pt scoring wines) are from here. So seeing vast tracts of land unused shows either how focussed these vinous Magellan’s are on discovering the finest plots on which to grow their vines, or indeed how many of these fantastic plots remain undiscovered. Either way, it has the distinct air of opportunity.

With this thought in my mind, and the goat finally starting to settle, we pulled up by one of those blocks of vines, about a mile in the distance, a square, modern concrete structure rose out of them. ‘That is where you are staying tonight’ our guide told us – a smart hotel, built exclusively for viticultural tourism, which included a polo field and a golf course. We had the run of the whole place, proving that this particular establishment was perhaps a bit ahead of its time – apparently, and viticultural tourism really hasn’t kicked off as a concept yet. Having spent so many hours getting to this spot, it wasn’t surprising, but I wouldn’t bet against it happening. Afterall, 40 years ago, Napa Valley was relatively unknown…

Everything where we stood, amongst the vines of Gualtallary, already some 1,000 metres above sea level, felt like it had been turned up to maximum. The sky was starkly blue, unblemished by clouds, the vines, a vibrant green, thriving in this extreme environment. The desert, for that is what it really is, which made up the rest of the landscape, a dusty backdrop, throwing these two colours into sharp relief. In the far distance, the Andes loomed, still snow-capped, despite the heat of the day.

This is when I first started to really take note of the sunshine. Our hosts had erected a gazebo for us to sit under, and like a typical Brit abroad, I hadn’t yet done my first round of suncream. This changed rapidly. I’m used to the sort of sun you can get whilst skiing, the snow on a bluebird day lulling you into a false sense of security and this felt even more extreme (a word which I will overuse, but seems to perfectly encapsulate the wine making involved here). You could feel your skin prickle, doubtless in part due to us being a pasty gang of sun-starved UK wine merchants in February, but it felt more intense than anything in the Alpes. It was, however, coupled with a strong breeze and relative coolness – I exist quite happily at 16 centigrade, but many of our party had to put jumpers on.

When I briefly studied viticulture, my lecturer always tried to instil that the greatest wines of the world were able to capture ‘cool sunshine’. For the first time ever, I felt this fully bought to life.

The experience of being shown a hole in the ground in a vineyard is not entirely alien to me, but it is quite unusual. When we visit Burgundy, Bordeaux, even Italy, there is no dash to a crater to prove your terroir – we know the Médoc is on gravel, the key to Burgundy is limestone and that the Italians would rather give you a nice lunch. This, however, is a frontier – there is nothing codified, little accepted wisdom and boundless land to discover. Evidencing your terroir, especially for Zuccardi with their Old World approach in putting the place above the grape is essential (buy a bottle and look for ‘Malbec’ listed anywhere, I dare you. Expect to find Paraje, Aluvional, Gualtallary or Valle de Uco, but if you see Malbec prominently written, especially on the new label, I’ll take you out for lunch). ‘Yes, it’s Malbec, duh. We’re in the Uco Valley’ is really what they’re saying. It’s a move to turn this into a normative assumption – it’s red Burgundy, of course it will be Pinot Noir, it’s Brunello, well then it must be Sangiovese. Zuccardi want to put the Uco in this category so you can focus on what really makes the wine exciting – producer and terroir.

Phew, after that long paragraph, I need a drink. But first, briefly, the hole in the ground. As I said, we’re very used to making assumptions about terroir in the Old World, but if you ask most wine enthusiasts, or even wine professionals, what makes the Uco Valley tick under the surface, they would likely draw a blank.

The key isn’t exactly simple either. In short, it’s calcareous granite. In French, you may have come across the word ‘Combes’, or Coombes in English, a sort of valley or gutter between peaks from which scree or éboulis is washed down the hillside creating prime viticultural land (Combes d’Orveau in Chambolle Musigny being a prime example). In Burgundy, this would be by a bit of rain off the Haut Côtes, a hill, In The Uco Valley, this is down the Andes, by tides of glacial melt water.. As they go, they change shape, you will initially find big boulders, which the water was unable to move far, but the further down you go, the more these big boulders either break up, or the finer stones are pushed. This phenomenon means that the wine at the top of the slopes tends to ripen earlier and create richer fruit flavours, those at the bottom of the mountain have more acidity, secondary characters and are more vertical.

‘Wait’, you might say, ‘is this not the wrong way around?’ Altitude usually means a dip in temperature. I thought the same, but these big boulders heat up a lot more and store more heat, causing the vines to wake up earlier and have a longer growing season, the cold air also rushes down the mountain, pooling more near the base. All it creates a very interesting, quite topsy turvy microclimate.

This calcareous granite is unique. Beautiful pink granite boulders like the below are wrapped up in a cement-like shell of limestone. It’s like the Côte-de-Beaune and the Mosel had a baby.

We finally got to stop for a drink. Two in fact. The vineyard in which we were stood was where Zuccardi source their Chardonnay – Fosil (you can see where the name come from with ancient soil like that) and the new cuvée Botanico (smell it, you will see why). Fosil is broader, richer, Botanico more poised and aromatic. They are both sublime bottles of Chardonnay, for very reasonable money and evidence some of this notion of Burgundy and Germany coming together under one roof. If it sways you, the most recent vintages have also been respectively awarded 96 and 97pts by RobertParker.com.

We finally got to stop for a drink. Two in fact. The vineyard in which we were stood was where Zuccardi source their Chardonnay – Fosil (you can see where the name come from with ancient soil like that) and the new cuvée Botanico (smell it, you will see why). Fosil is broader, richer, Botanico more poised and aromatic. They are both sublime bottles of Chardonnay, for very reasonable money and evidence some of this notion of Burgundy and Germany coming together under one roof. If it sways you, the most recent vintages have also been respectively awarded 96 and 97pts by RobertParker.com.

Day 2 | Part 2

All the days we had in Argentina were special, but I wanted to put particular emphasis on the second half of this one.

Having absorbed more information about the terroir of the Uco Valley than a dry limestone bedrock, we were promised a big lunch. The hotel, even from that distance, looked very inviting and we had been told that there was a pool and a bar – what else does one need in life?

Therefore ‘We’re going into the Andes’ as a proclamation met with consternation and intrigue. ‘There’s a farmer up there who will give us lunch’.

I grew up on a farm, so I know that, depending on the proprietor, this meant we were either going to eat several whole animals, or be served a feeble amount of basic fare – bully beef, lettuce leaf, stale bread. My grandparents were not gastronomes.

Fortunately, it was the former, but the real reason for our ascent soon became clear. As you leave the Uco Valley and go into the mountains proper, you chart a dust track which is largely surrounded by vines, with the last sign on the right reading ‘Catena Zapata’. Beyond this was 30 minutes of trail, with the odd sign of life – a house here, civic building there – and almost zero greenery. Without the vibrant green of the vines, the landscape’s colour palate, like an aged Claret, had faded mostly to brown.

That was, until we hit an oasis. In instant, everything became green, grass, trees, bushes. A few minutes more and there were cows, munching on a verdant patch beside our track and surrounded by shrubbery, the sort of bucolic scene you might get on an English postcard.

We forded a stream, the first running water we had seen for lord knows how long, and pulled up outside a ranch. In an almost Wild West fashion, suspended from a wooden arch with a gate in it, swung a sign, reading ‘Estancia San Pablo’, and behind this, swept a bank of vines leading up to the farmhouse.

Yes, we were here to lunch, but we were also here to drink – not just to drink though, to consume one of the most fascinating bottles in the entire trip.

Walter Scibilia, to whom this estate belonged, is gaucho through and through. All of his children greeted us in traditional gaucho dress and told us how they frequently make their long journey to school on horseback.

Indeed, Walter’s gaucho roots go so deep that, when he attended the University of Mendoza to earn his diploma in oenology, he did so in full gaucho dress – something which he carried through to graduation, attracting the ire of the university, who deemed it inappropriate attire and refused to award the qualification.

Walter sued for discrimination and won, but instead of taking the money, requested that they instead use it to pay for his wine master’s degree in Montpellier. Now an exceptionally competent viticulturalist, he took his expertise on tour, working across Bordeaux and California, before returning home to start this, his own project, in 2004.

I’ll admit that I’ve never had Uco Valley Pinot Noir before, the mention of it would have turned me off entirely (far too much heat, low acid, jammy… Horrid) but this was captivating. The alcohol here is just 12.8% and if I were backed into assigning it a style, I’d opt for Chambolle. The aromatics, which follow to the palate, are explosive – bright, tensile red fruit with violet, rose petal and white flower. The PH is an Old World 3.5 and the structure impressive enough to age for a decade.

Un Lugar En Los Andes is the highest commercial vineyard in the Uco Valley, a staggering 1,700 metres above sea level. Whilst down below, we felt the occasional need to wrap up against the wind, up here, if you were out of the sun, it was positively chilly.

Any notion of chill, however, was quickly dispelled by three goats being roasted over an open fire, and round after round of empanadas coming out of another wood fired oven. They have 900 vines in this oasis, and one thing I would like to impress upon you is that Argentina, like Chile, like Napa or many of the other very dry parts of the viticultural world, relies heavily on irrigation. Walter’s vines were totally dry farmed, such is the gift of this little patch of green land, surrounded by desert.

Alongside the magical Pinot Noir, of which there are but 600 bottles made (in a good year), they also make a stunning Malbec. Lean, aromatic and fizzing with energy – it was about as far from the commercial image of the grape as you can find. 2018 was their first official release and 2019 was the first to properly find its way into the market, so this project is still exceptionally young.

They don’t come cheap, but if you want to experience something unique, they are worth hunting down. We are so used to trying wine from places where the entire region is packed out with vines, so to be able to get wine for such an isolated, extreme and beautiful spot, where the grapes has not, likely will not and probably cannot express itself for miles around, it’s one of those rare, thrilling experiences.

After our feast, we headed back down the mountain, to finally bask in our hotel pool and frustrate the two bartenders. I don’t think they’ve ever made so many Pina Coladas in one evening in their entire lives…

Day 3

If you’re still reading this, you’re probably starting to think that this trip is just an excuse to be a lush, and you are to the greater extent, correct. However, to avoid casting aspersions over the entire UK wine trade, on day 3, we embarked on something academic.

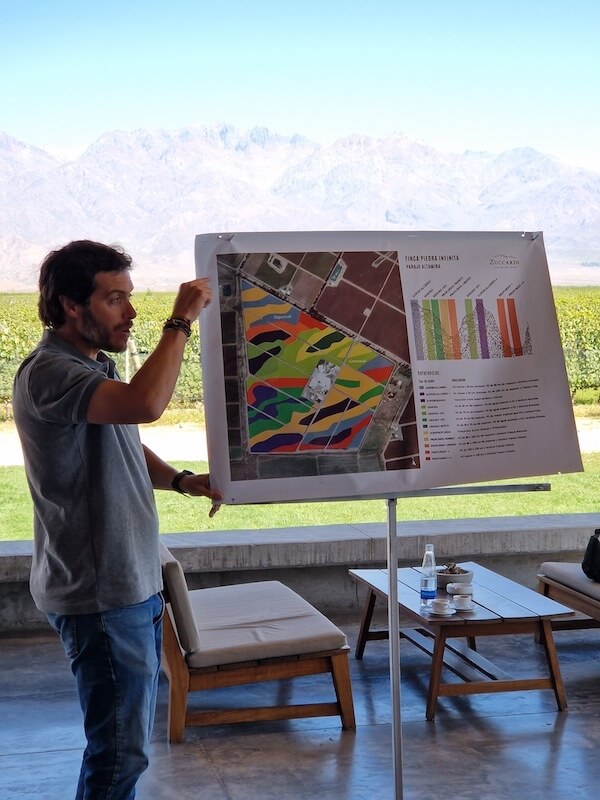

It still involved wine, of course, but we were taken to and through Zuccardi’s striking winery in order to learn more about the processes involved in their wine production, and to see the fabled ‘Piedra Infinita’ vineyards.

The fairly literal translation of this name is infinite stones, a name given to the site, Sebastian Zuccardi explains, because when they began construction, they were told it might take about 30 lorry loads to clear enough of the enormous rocks in the area for the winery to be built and vineyards planted.

It took over 1,000.

How’s that for terroir. The winery itself looks part fortress, part monolith and part Bond villain lair (Sebastian insisted that the dome on the top wasn’t for launching ballistic missiles…) but in a slightly brutalist fashion, compliments the mountainous backdrop exceptionally well.

You read a lot about these iconic wines, and indeed I did – I even drink them a few times before going out (research, of course), but until you are in the place, it is impossible to appreciate the scale. I think we are all guilty of assuming that New World wine is made in enormous quantities, or certainly far larger and more homogenous volumes than their European cousins, but to see the vineyards around the winery, from which Zuccardi make their flagship label – Piedra Infinita, Gravascal and Supercal, was a bit like going to the Côte de Nuits for the first time. The area under vine was tiny.

Not only was it small, it was also meticulously delineated. At the risk of sounding too biblical, in the beginning, Zuccardi just made one cuvée, Piedra Infinita, from these special vines around the winery, but in 2015, having dug many, many holes in the ground, they were able to delineate three parcels of land, which they begun to vinify separately.

Not only was it small, it was also meticulously delineated. At the risk of sounding too biblical, in the beginning, Zuccardi just made one cuvée, Piedra Infinita, from these special vines around the winery, but in 2015, having dug many, many holes in the ground, they were able to delineate three parcels of land, which they begun to vinify separately.

Gravascal is the product of a plot of deeper soil, with those limestone-covered rocks beginning to become dense 60cm below the surface. With Supercal, they begin almost immediately. Both are just 0.7 hectares and make roughly 1,000 bottles a year – proper Burgundian numbers.

The wine itself is very austere. As with the whole Zuccardi range, it is not about the grape, it is about the site and this once again dismisses the notion that Malbec should be generous, rich and ready to go. This require age, more age than anything else in the Zuccardi portfolio, but the results of that patience are more infinite than the stones in the vineyard.

Right – academia. This is where I manage to rewrite your image of the wine trade and how we comport ourselves. Following a tour of the winery and vineyards, Sebastian wanted us to taste all of his wines in sequence to build up a total picture of their various terroirs and what they have achieved (and indeed, are trying to achieve). Sat in the missile dome across a huge horseshoe table, we were served nearly 30 wines from across various sites in Argentina, every one with their own distinct characters, then asked to make comment. It was as edifying as it was challenging – akin to sitting down with a great Burgundy producer like Thibault Liger-Belair and tasting through his 50 or so wines, but with a far smaller understanding of the terroirs at work. It did, however, once again keenly show the direction in which the Zuccardis are taking their viticulture, and trying to take Argentinian fine wine as a whole.

After the hard work was done, we were taken downstairs to the winery’s beautiful restaurant, to sit and eat steak, whilst looking through the enormous glass windows at the snow-capped mountains. We had, after all, earned it.

My father is a beef farmer, and has been his entire life, so I expect I will be thrown out of the family for saying this, but it was the best steak I’ve ever had. Sorry dad.

My father is a beef farmer, and has been his entire life, so I expect I will be thrown out of the family for saying this, but it was the best steak I’ve ever had. Sorry dad.

Some more revelry followed, including a tango display put on for us at an enchanting outdoor restaurant in Mendoza, but the next morning we were forced to pack up and leave early, to make the long voyage through the mountains and into Chile…

Show this to my good friend William Hancock’ at World Wine Consultants. It’s an outstandingly informative blog and deserves wider circulation.